The Emotion and Behavior Lab studies how people connect. We take a multilevel approach to studying the motivational states (emotions) that drive people to seek social connection and the behaviors that create those connections. Social connection begins with moments of interpersonal behavior: shared laughter, the exchange of interesting ideas, the achievement of synchrony. The EB Lab studies the form and function of the nonverbal and verbal behaviors people use to understand each other and build bonds. But no social connections exist in isolation: they are links in an interconnected and dynamic network of social connections. That’s why we also study how people build their social networks. We zoom out one more time to consider what happens when people leave one social network for another, and what happens when enough people move around to create culturally diverse communities. No matter what level we’re focusing on (dyadic interaction, social networks, culture), we assume that all behavioral strategies have tradeoffs, and the optimal social behavior is a function of the social context and a person’s motives.

Ongoing research lines

nonverbal behavior: Forms and functions

Laughter is a ubiquitous social signal that can smooth interactions (Wood & Niedenthal, 2018). We observed how much people laughed across conversations with multiple strangers and found that laughter is a stable trait: some people laugh more, and some people laugh less, regardless of who they are with (Wood et al., 2022). And the more people laughed, the more similar others felt to them. This suggests an important function of laughter is to build social connection.

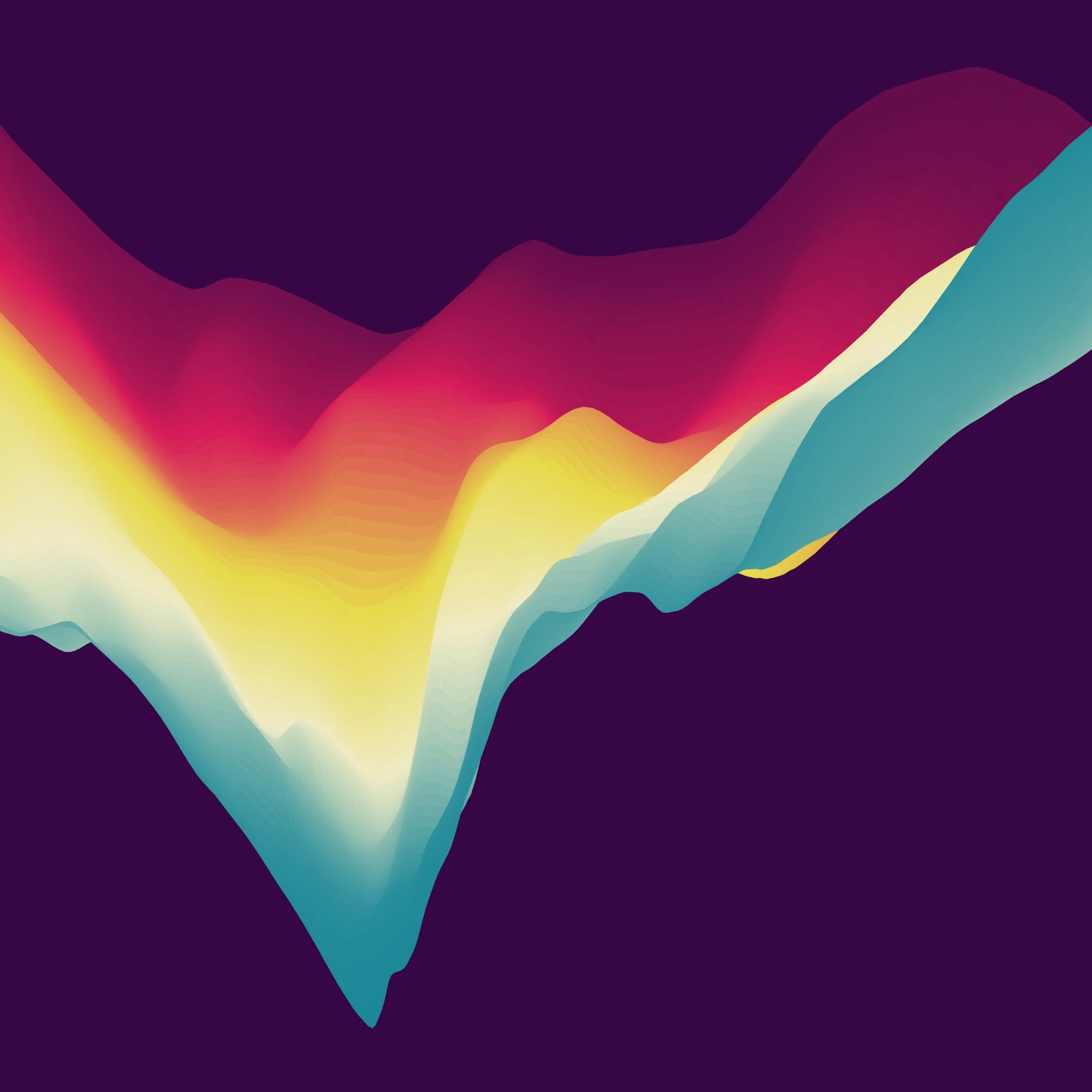

Spectrograms of 3 spontaneous laugh samples produced by participants in one of our studies (Wood, 2020). Notice the differences across the laughs—laughter takes many forms!

The physical form of a signal (how it looks or sounds) can also tell us what those functions might be. We identified three distinct social tasks accomplished by laughter (and their visual analogue, smiles; Martin et al., 2021): rewarding the desirable behavior of others (reward), soothing and signaling nonthreat (affiliation), and indirectly challenging the status or behavior of others (dominance). One study we conducted related participant judgments of the social intentions of 400 laughter samples to the laughs’ acoustic features, which we extracted using acoustic analysis software (Wood, Martin, & Niedenthal, 2017). Unique acoustics predicted the 3 proposed social functions, suggesting systematic changes to the voice during laughter can convey reward, affiliation, or dominance. These relationships often depended on the sex of the expresser: louder laughter, for instance, was perceived as more affiliative in males, but less affiliative in females. In a recent naturalistic study (Wood, 2020), we found that pairs of people laugh differently during rewarding, affiliative, and dominant conversations.

Just as nonverbal signal production is flexible, so too is the perception of nonverbal signals. For instance, kids and adults track targets’ facial and vocal expressivity and update their responses accordingly (Plate, Wood, Woodard, & Pollak, 2019; Woodard et al., 2021). We have also shown that dynamic facial expressions are perceived differently when combined with learned conventional gestures like thumbs up (Wood, Martin, Alibali, & Niedenthal, 2018).

We also examine the form and function of interpersonal synchrony (Wood, Lipson, Zhao, & Niedenthal, 2021). Matching the behavior of another person can help build connection by enabling mutual understanding, making the interaction more fluent, and creating a sense of similarity, but more synchrony is not always better. We think people use synchrony when it is necessary—for instance, when communication has been disrupted (Zhao et al., 2022)—but by doing so, they sacrifice the exchange of new information.

Conversation: being understood and being interesting

This is our newest line of research. How do people decide what to say during conversation? We are examining the potential tradeoff between saying predictable things (e.g., making small talk or sharing normative opinions) and saying interesting things (e.g., sharing a surprising anecdote or making an unexpected association). How do people navigate this tradeoff and what are the costs and benefits of prioritizing one goal or the other?

social networks: the explore-exploit tradeoff

Moments of social connection and communication add up to enduring relationships and social communities. We use real-world social networks, naturalistic crowd observation, laboratory interactions, and agent-based modeling to explore this topic.

We are particularly interested in trait and state tendencies to explore one’s social environment. How and why do some people become well-connected to their communities (e.g., Wood, Kleinbaum, & Wheatley, 2022)? An ongoing field project uses computer vision to analyze the movements of people at a get-to-know-you mixer to see if we can predict who will end up well-connected or socially isolated months later. Ongoing and upcoming studies supported by an NSF CAREER grant use interactive games, lab experiments, and mobile sensing to understand the tradeoff between exploring one’s social environment and deepening existing ties. Another project supported by the Templeton-funded Primals Award examines the causes of individual differences in the motivation to explore the social world.

cultural diversity: adapting to differences

Greener countries are higher in ancestral diversity, meaning a greater number of source countries contributed to their current populations.

What happens when entire social networks “interact” with other social networks? In other words, how does cultural mingling influence social behavior? We study the consequences of being in a culturally diverse community. We argue that cultures arising from the intersection of other cultures, such as in the U.S., initially lacked a clear social structure, shared norms, and a common language (Niedenthal, Rychlowska, & Wood, 2017). Such cultures would have to increase their reliance on nonverbal signals, establishing a cultural norm of expressive clarity. For instance, 83 countries have made significant contributions to the current population of the U.S., a country high on ancestral diversity, but only 5 countries contributed to Russia's current population, making it low on ancestral diversity. We re-analyzed data from 92 cross-cultural emotion recognition studies (involving 82 unique countries) and showed that facial expressions from more heterogeneous cultures are better recognized cross-culturally than those from homogeneous cultures (Wood, Rychlowska, & Niedenthal, 2016). People from heterogeneous backgrounds also laugh and smile more frequently (Niedenthal, Rychlowska, Wood, & Zhao, 2018), which we suggest facilitates the formation of new social ties and communicates trustworthiness to strangers.

We recently used social network analysis to demonstrate that exposure to ancestral and present day diversity influences people’s ability to form new social ties (Wood, Kleinbaum, & Wheatley, 2022). Highly diverse socio-ecologies are higher in relational mobility, meaning people in diverse contexts have more unstable social networks. Friends and social ties are gained and lost more easily. People who were previously exposed to diverse environments may therefore be better-prepared to form new social ties when they enter a new community.